RVCL-S stands for retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy and systemic manifestations. Since RVCL is such a rare disease, it also has been referred to by several names: retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy (RVCL), cerebroretinal vasculopathy (CRV), hereditary endotheliopathy, retinopathy, nephropathy and stroke (HERNS), and hereditary vascular retinopathy (HVR). The latest designation (RVCL-S) is the most accurate description of the disease process.

This disease is an inherited disorder with a change in the DNA of a gene. Symptoms initially begin at middle age and primarily affect the eye and brain. As an “autosomal dominant disease,” it affects both males and females equally. A person with RVCL-S has a 50-50 chance of passing it along to any of their children. If a son or daughter does not inherit the mutant gene, they and their offspring will not get the disease and are safe.

Causes

RVCL-S is an ultra rare genetic disease caused by a mutation in the TREX1 gene that lies on chromosome 3.

DNA consists of two strands, with one strand being inherited from each parent. Thus, RVCL-S individuals carry a normal gene on one strand and a mutated TREX1 gene on the other; that is why individuals with a TREX1 mutation have a 50% chance of passing it along to each offspring.

Exactly how a TREX1 mutation causes damage to small blood vessels is unknown.

The TREX1 gene produces the TREX1 protein. In its protein form, TREX1 is localized inside cells in a maze of ‘sacks’ or membranes called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ER is attached to the nucleus of each cell and serves important roles in manufacturing and releasing proteins needed by the body. In RVCL-S, TREX1 mutations occur in the last one-third to one-fourth of this rather small but key protein. This type of TREX1 mutation results in a shortened, incomplete protein.

The tail of TREX1 is important for keeping it localized to its normal place in the ER compartment of cells. The loss of its tail causes it to mislocalize and spread throughout the cell. Because it loses its ability to stay in its proper location, we referred to this as “TREX on the loose.”

This type of dysfunctional TREX eventually harms certain cells.

The symptoms RVCL-S patients develop indicate that when TREX1 mislocalizes it particularly affects the innermost cells that line blood vessels (called “endothelial cells”).

Part of the goal of the RVCL-S Research Center is to conduct basic research on TREX1 to better understand its biochemistry and functions and how that may relate to RVCL-S.

Symptoms

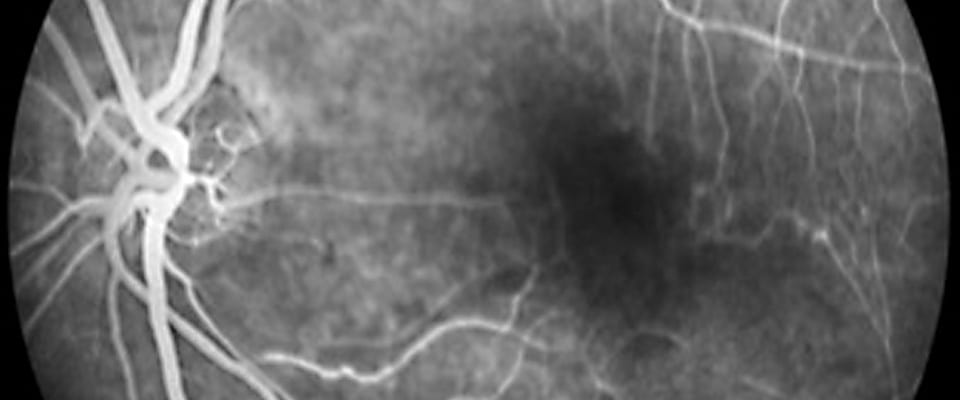

RVCL-S symptoms usually begin in middle age (35-50 years) with eye issues such as an increasing number of “floaters” and “blind spots.” It then progresses to parts of the brain and other organs.

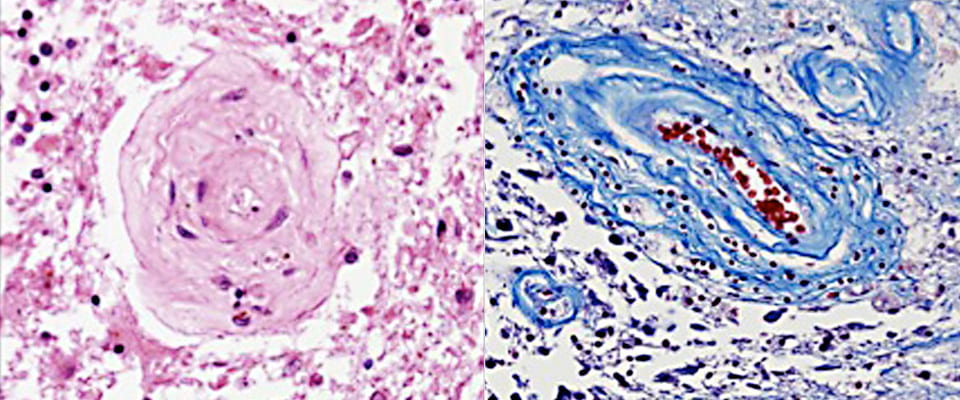

The main pathological process of RVCL-S is that small blood vessels prematurely “drop out,” that is, deteriorate and disappear. This leads to mini- strokes called “micro-infarcts” in tissues. Initially, the loss of blood supply particularly seems to affects both the eye (retina) and the brain (white matter). These organs have key functions sensitive to any type of disruption in blood flow.

The progressive vessel “drop out” leads to increasing vision loss and larger brain infarcts or tumor-like lesions, especially if the mini-strokes are clustered.

Diagnosis

Because RVCL-S is so rare, it is often misdiagnosed as “bad” multiple sclerosis, diabetic retinopathy, a brain tumor, or a vasculitis (blood vessel inflammation).

However, correct diagnosis of RVCL-S can be made by a genetic test that conclusively establishes if a patient has the disease.

Treatment

We are focused on establishing and coordinating studies to better define clinical course and pathology, as well as (most importantly) identifying therapeutic agents for symptomatic RVCL-S patients.

There currently is no treatment for RVCL-S; however, there is a way to prevent transmission of the disease to the next generation. Please contact us if you’d like to know more about reproductive choices or clinical trials.

For additional information on RVCL-S, see our review on the website of the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD).